| Epoch: Romantic

Country: Austria |

Scientific direction: Mag. Zsigmond Kokits |

[naar inhoudsoverzicht korte biografieen]

[terug naar inhoud Schubert-biografie 2]

inhoud:

- Schubert's method of working

- The symphonies

- The church music

- The Austrian church music before Schubert's time

- Franz Schubert and the church music

- Schubert's early church compositions (till 1816)

- The church compositions after 1816

- Schubert's setting to music of liturgical texts

- The question about Schubert's religiousness

- The lieder

- The German lied in the 18th century

- Schubert's examples

- The first creative period (till 1816)

- The lieder of the middle creative period

- The lieder of the last creative period (1824-1828)

- Polyphonic lieder

- The piano music

- The chamber music

WORKS

| [Biography] | [Schubert memorial places] |

Schubert's method of working

He took notes and made sketches and when he - as reported - wore his glasses even asleep, it could probably be explained by the fact that he wanted to be ready at any time to record sudden bright ideas - music-paper and writing things were always ready. But the final recording was usually made in one stroke, only a few of his works (for instance the Mass in A flat major) were composed during a longer stretch.

Bad circumstances seem to have stimulated his compositional work: In

1815 and 1816, as external duties oppressed him the most, he sought refuge

in composing and wrote approximately 250 lieder and four symphonies.

As he dated his compositions usually conscientiously, it might be possible

to compile a journal of his work. For July 1815, the most prolific month

in Schubert's life, it would look like this (in parentheses the numbers

of the Schubert work's list by Otto Erich Deutsch):

| 2nd | Lieb Minna (D 222) |

| 5th | Salve Regina (D 223)

Wanderers Nachtlied I (D 224) Der Fischer (D 225) Erster Verlust (D 226) |

| 7th | Idens Nachtgesang (D 227)

Von Ida (D 228) Die Erscheinung (D 229) Die Täuschung (D 230) |

| 8th | Das Sehnen (D 231) |

| 9th | Completion of the Singspiel „Fernando" (beginning on June 22nd) (D 220) |

| 11th | Hymne an den Unendlichen (D 232) |

| 12th | First movement of the Symphony No. 3 (beginning on May 24th) |

| 15th | Geist der Liebe (D 233)

Der Abend (D 221) Tischlied (D 234) Second movement of the Symphony No. 3 (beginning) |

| 19th | Symphony No. 3 finished |

| 22nd | Sehnsucht der Liebe (D 180) (new version) |

| 24th | Abends unter der Linde (D 235)

Abends unter der Linde II (D 237) Die Mondnacht (D 238) Das Abendrot (D 236) |

| 26th | Singspiel „Claudine von Villa bella" (D 239) (beginning) |

| 27th | Huldigung (D 240)

Alles um Liebe (D 241) |

When he was no longer tied down by the teaching profession, he composed usually in the morning during six to seven hours with highest concentartion. At that time, a visitor had not the slightest chance: „When you come to see him during the daytime, he says 'hello, how are you? Fine' and goes on writing, whereupon you leave..." - reports the friend Moritz von Schwind.

The symphonies

Just some years ago, the musicology still disagreed on the question about the numbering and the chronological order of the last Schubert symphonies.

The chronology of the symphonies

| Symphony fragment (only 30 measures) | 1811 | |||

| Symphony No. 1 D major (D 82) | 1813 (August 29th to October 28th) | |||

| Symphony No. 2 B-flat major (D 125) | 1814/15 (December 10th to March 24th) | |||

| Symphony No. 3 D major (D 200) | 1815 (May 24th to June 19th) | |||

| Symphony No. 4 C minor, „die Tragische" (D 417) | 1816 (finished on April 27th) | |||

| Symphony No. 5 B-flat major (D 485) | 1816 (September to October 3rd) | |||

| Symphony No. 6 C major (D 589) | 1817/18 (October to February) | |||

| Symphony fragment in D major (D 615) | 1818 (summer) | |||

| Symphony fragment in D major (D 708A) | 1821 | |||

| Symphony fragment in E major (D 729) | 1821 | |||

| Symphony B minor, „the Unfinished" (D 759) | 1822 (beginning: October 30th) | |||

| Symphony C major, „the Great" (D 944) | 1825 (summer) | |||

| Symphony drafts D major | 1828 |

The first six symphonies succeed continuously one another, they are

from Schubert's first great creative period and represent respectively

different types of the genre.

Just a few months after he had finished the 6th Symphony, Schubert

started composing a new one. But this time, only piano sketches were the

result. For none of the earlier symphonies there were similar drafts -

Schubert departed for the first time from his habit to compose immediately

in partition: One of several little signs of the creative crisis of the

middle period around 1820. Two other fragments from 1821 give us the basis

for the assumption that Schubert ripened concerning the symphonic composition

during this „years of crisis". The result was then reflected in the symphonies

B minor and C major. This works represent without doubt a new aesthetic

level among Schubert's orchestral works.

The Symphony in B minor is generally called „the Unfinished", because

it has uncommonly only two movements. But the first measures of a third

movement are preserved and prove as a matter of fact that the work is unfinished

in the form with two movements.

In summer 1825, Schubert started to compose his last finished symphony. As he was working on the composition also in Gmunden and Badgastein, it was occasionally called Gmudner or Gasteiner Symphony. In concert programs and on the occasion of disc recordings the symphony has usually the number 7. However, the numbering of the symphonies comes not from Schubert, but from Johannes Brahms, who has prepared these works in 1884/1885 for the first complete edition of Schubert. He numbered the complete symphonies at first, therefore the great C major Symphony follows the sixth. The earlier composed „Unfinished" was placed as „addendum" after the seven complete works and received the number 8. This count does not correspond to the chronology, but it was transmitted to this very day - and caused confusion among the concertgoers.

None of the Schubert symphonies were performed in a public concert during

the lifetime of the composer. Schubert composed the early symphonies for

an amateur orchestra and after a single concert in a private circle they

disappeared again in the drawer of the composer. The „Unfinished" was performed

for the first time only about fourty years after its creation, on December

17th 1865, at the Wiener Redoutensaal, the court conductor Johann Herbeck

conducting.

In 1824, Schubert gave the partition of the two movements to the Steiermärkische

Musikverein Graz (Styrian musical society Graz) as a reward for the honorary

membership bestowed on him a year before. His friend Anselm Hüttenbrenner,

the director of the Steiermärkische Musikverein, preserved the partition

at his place. Herbeck, who heard many years later by chance about the donation,

brought the autograph to Vienna to perform the work.

The great C major Symphony had to wait „only" twelve years until it was premiered in March 1839 by Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy in Leipzig.

The church music

The Austrian church music before Schubert's time

Although there were no special orders concerning the church music,

Joseph II influenced it by the court decree of February 23rd 1783 rearranging

the parishes in Vienna and so also the regulations of the services. These

measures subsumed under the catchword „Josephian reforms" continued to

be valid in letter under Franz I, but loosenings were already noticed.

From 1820 on, they were successively repealed. The „good Emperor Franz",

often so called by the people, was not affected by enlightening ideas.

The Enlightenment lost ground to an increasing extent by the penetration

of the Romanticism and the German idealism.

Franz Schubert and the church music

At the parish church Lichtental, just two minutes away from Schubert's birthplace at Nußdorferstraße 54, Schubert became very early acquainted with the church music and its current style. His first teacher, Michael Holzer, was regens chori at the church since 1794. He asked Schubert certainly several times for a church work. Holzer, well-grounded in counterpoint, is supposed to have assured Schubert's father with tears in his eyes: „Each time I wanted to teach him something new, he knew it already."

At the Wiener Stadtkonvikt his teacher Antonio Salieri exerted the most

important influence in church music on Schubert. In particular by comparing

the smaller church works of the two composers, his influence on the young

pupil is surprising. After all, the court conductor knew Schubert already

before his admission in the court orchestra as choirboy and from June 18th

1812 to the end of 1816 he was his pupil.

Schubert's early church compositions (till 1816)

Of course, Schubert seized the opportunity to come out with church works. So his first work, the Mass in F major (D 105), was performed at the church of Lichtental in autumn 1814. Ferdinand Schubert mentioned this performance in his writings: „It was a touching sight to see the young Schubert, the youngest among all present musicians at that time, conducting his composition."

In the year 1815, rich in lieder, two masses were composed: the first mass in G major (D 167) between March 2nd and March 7th and the second in B-flat major (D 324). The G major mass is from the type a Missa brevis, a typical „country mass" for mixed choir, strings and organ. It is considered as his best of the four early works. Schubert started to compose the B-flat major mass on November 11th. We do not know when he finished it, but it was probably performed at the end of 1815 at the church of Lichtental. From the style, it is bound to the classical masses of Joseph Haydn.

The fourth mass in C major (D 452), the so-called „thorough bass mass", was composed in June and July 1816. Schubert published this work in 1825 and dedicated it to his teacher Michael Holzer. It was performed on September 8th 1825 at the church of St. Ulrich (today „Maria Trost" in the 7th district of Vienna). The instrumentation is equivalent to the so-called „Viennese church trio" (two violins and one bass).

The church compositions after 1816

The German requiem

In autumn 1818, Schubert turned again to the church music by the German requiem (D 621). For a long time, this work was considered as a composition of Ferdinand Schubert. For Ferdinand had to set a funeral mass to music for the vice-director of the Imperial and Royal orphanage, J. G. Fallstich. He asked his brother, who was with the Esterházy family in Zseliz at that time, to compose such a work and Franz did him the favor. Ferdinand performed the requiem at the orphanage already on September 18th of this year. In 1826, he published, Diabelli & Co publishers, the work - with knowledge and consent of his brother - under his own name and dedicated it to Fallstich. The text of the requiem comes from a prayer-book drawn up by Franz Seraphicus Schmid, a prelate and canon of St. Stephan.The Mass in A flat majorr

In November 1819, Schubert started working on his Missa solemnis, the Mass in A flat (D 678), and he finished it on December 7th 1822. Three years later, on April 7th 1826, he applied with this mass in vain for the vacant post of vice-court conductor. It is true that the court conductor considered the mass as good, but he found that „it is not composed in the style, that the Emperor loves". Probably at the end of 1825, Schubert submitted the mass to a thorough-going revision for his application: He recomposed entire parts, even the fugue „Cum Sancto Spirito" and the „Osanna".The German Mass

One year after his vain application he composed the German Mass (D 872). The text comes from Philipp Neumann (1774-1849), professor at the Imperial and Royal polytechnic institute in Vienna. For the composition, Schubert received 100 fl. in Viennese currency. The German Mass became one of the most popular works by Schubert, though it was rejected for the public use in church at first. Only in the middle of the last century it was released in Austria.The great E flat major Mass

In June 1828, Schubert started composing his last mass (D 950). It was a commissioned work for the „Verein zur Pflege der Kirchenmusik" (society for cultivation of church music) of the parish Alsergrund (today 9th district), which regens chori, Michael Leitermayer, was a schoolmate of Schubert. After Schubert's death, it was performed at the parish of Alsergrund on October 4th 1829 and on November 15th at the church St. Ulrich.The later church music of Schubert shows a wide development anticipating already Bruckner. The early liturgical works are under the important influence of the masses by Joseph Haydn and other Viennese church musicians, but a new style is heralded in the A flat major Mass. With the overcoming of the classical style Schubert found in the church music, as already before in other musical genres, his own style interspersed with romantic elements and so a new musical interpretation of the liturgical text. The sound spectrum with its instrumental couplings specific to Schubert gives an inner shining to his late works - particularly impressive in the Kyrie of the E flat major Mass.

Schubert's setting to music of liturgical texts

Such offenses against the text were tolerated in silence at that time. Otherwise his teachers Holzer and Salieri, but particularly his in religious things dogmatic father would have pointed out the prohibition of text shortenings to Schubert and his church music would not have been performed in the transmitted form.

So far, the possible reasons for text alterations in Schubert's church

works were debated almost solely in respect of the masses, particularly

concerning the ellipsis of the words „credo in unam sanctam catholicam

et apostolicam ecclesiam" at the end of the Credo. It is uncontested that

this ellipsis is not a mistake. Where Schubert could not set a definite

text to music for ideological reasons - such as in parts of the „Credo"

of the mass - he struck it out. He left texts without personal character

of confession as they are.

The question about Schubert's religiousness

Schubert grew up in a religious entourage marked by a strict Catholic father. He went regularly to the services at the nearby church of Lichtental and sang as choirboy at the Konvikt. At school he submitted to the requirements, in religious education he got full marks. According to Anselm Hüttenbrenner's reminiscences, Schubert had at the Konvikt „a pious nature and believed firmly in God and in the immortality of soul. Some of his lieder reveal clearly his religious sense".

There are no definite statements of Schubert about his religiousness,

only indirect comments as reaction to what he read and heard are preserved

in his diary and letters.

A slow reorientation and emancipation nourished by his free-thinking

brother Ignaz and the dogmatically hampering and one-sided relations in

his family came about in the adolescent Schubert.

Schubert became successively estranged from the institution church and

the religious roots of the Catholic piety of his youth. It appears that

Schubert developed more and more a pantheistic religiousness stimulated

by humaneness and a philosophical way of thinking.

The Lieder

The importance of Schubert's lieder lies doubtless in the balanced unities and synthesis of poetry, singing and accompaniment. This unity arose from Schubert's aesthetic conception which brought by its perfect development an own history of activity about for the following compositions of lieder and won recognition as genre of the art song. The music has no longer just the purpose of accompaniment of poetry, which prescribes the structure, the rhythm and the content. Not only the melodic ability of the voice, but even the piano accompaniment, neglected by the Berliner Liederschule (Berlin lieder school) for instance, becomes a support of the mood and a mediator of the poetic content.

The German lied in the 18th century

So the composer had to submit more or less to the dictates of the poet's text. In Koch's view, the composing without repetition of the melody and the accompaniment in each stanza, as it was put into practice for the first time in 1775 by Johann André in his „Leonore", was permitted only in ballads, because otherwise the ballads set to music, particularly if they had approximately 30 to 40 stanzas, were found boring.

It is true that it was allowed to vary the melody and to adapt it to

the affect of the text, but the division of the model into stanzas had

to be discernible. Another „legitimate" possibility of setting to music,

quasi a cross between lied in stanzas and through-composed lied, was the

„varied lied in stanzas".

Schubert's examples

Three musical currents or stylistic movements exerted an influence

on Schubert as composer of lieder: the so-called „Berlin", the „Viennese"

and the „Swabian lieder school".

The Berlin lieder school

In Germany, the so-called „second Berlin lieder school" had the most important influence on the aesthetic conception of the lied. Its most important exponents were Johann Friedrich Reichardt (1752-1814) and Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758-1832) with their friend and prince of poets Goethe. Their principles were formulated by the founder of this lieder school, Johann Abraham Peter Schulz (1747-1800). In the preface of his edition of the „Lieder im Volkston" of 1785, he demands to „make good texts of lieder generally known", to set them to music so that a new lied seems to be well-known by the audience. The lied has to be distinguished by being „singable and popular" and has „never to rise above the course of the text" by the melody and its progressions. Strictly speaking, the second Berlin lieder school supported nothing else but the principle of the simple lied in stanzas. The piano had to accompany the singing voices with chord arpeggios and repetitions. The coexistence of voice and accompaniment was characteristic of the Berlin lieder school. It has survived into the 19th century. Some copies of Reichardt's lieder show that Schubert dealt with lieder of this school.The Viennese lieder school

The „Viennese lieder school" around Joseph Anton Steffan was the nearest for Schubert. Despite great names such as Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, which lieder Schubert knew, it played a rather minor part. Generally, the Viennese lieder are influenced mainly by the Italian aria, particularly by Mozart's, and so in the musical arrangement and form more free than those of the Berlin lieder school.The Swabian lieder school

The third movement, the South German or „Swabian lieder school" exerted the most important influence on Schubert. Its main exponent Johann Rudolf Zumsteeg (1760-1802) was close to the poet and aesthetician Christian Schubart and in particular to Friedrich Schiller. The adherents of this movement demanded a more free treatment of the text and piano accompaniment and imposed no strict rules on themselves. They set less lieder in stanzas to music than through-composed ballads, which received a special musical treatment. Schubert was particularly attracted by this method of setting to music. With Zumsteeg, which anthology of „little lieder and ballads" he had got to know and wanted to „set in another way", he became acquainted not only with the free and varying disposability of keys, but he adopted from him, as the example of Hagars Klage (D 5) shows in particular, also the form and structure of the lieder, the preference for specific texts and the favor shown to poets like Schiller, Kosegarten, Matthisson and Hölty.Only in 1817, the Swiss music educationalist Hans Georg Nägeli (1773-1836) formulated and demanded the aesthetic conception - at first only gingerly supported and converted into lieder and ballads by the Swabian lieder school - that the poetry requires the interpretation by music so that the relations of language and music become „dialectical".

The first creative period (till 1816)

The first lieder

At the Konvikt, Schubert composed some ballads such as the Leichenfantasie (D 7) or the diver (D 77), with which Schubert quitted Zumsteeg's example for the moment in 1813. In later settings to music such as Die Erwartung (D 159) and Ritter Toggenburg (D 397), he leaned on Zumsteeg another few times. A through-composed lied by the fifteen-year-old boy is Der Jüngling am Bache (D 30). An early lied in stanzas Klaglied (D 23) after Rochlitz gets into this list as well as the two Italian arias D 76 and 78 after Metastasio.The early through-composed lieder and ballads show as essential compositional characteristic feature an additive succession of lied-like, aria-like and recitative sections forming a whole.

The „birth" of the romantic lied

After leaving the Konvikt in 1814, thirteen settings to music of poems by Matthisson were added: varied lieder in stanzas such as Erinnerungen (D 98) and Der Geistertanz (D 116) or through-composed lieder such as Adelaide (D 95). All this lieder, showing a certain variety in their choice, are attempts to find a new lyrical expression. Only with the lied Gretchen am Spinnrade (D 118), composed on October 19th 1814, the lied was born that determines our conception of a lied still today. Some Schubert researchers even think that the genre of the romantic piano lied as such is created by it.Schubert ties separate lied parts by homogeneous musical movement, keeps them together by it, such as dramatic scenes are kept together by a homogeneous scenery, and refers so each detail in the lied to a fundamental situation. The setting to music of the first poem by Goethe was not the last one: Aside from multiple settings to music, their number will grow to over sixty in the course of Schubert's life.

The „years rich in lieder" 1815/1816

The years 1815 and 1816 are considered to be the most prolific „lieder years" of Schubert. He set then more poems to music than during the following years. It will always be a mystery how Schubert was able to compose with such an intensity after nine hours of service as supply teacher. As if this compulsion would have lent wings to the young composer all the more. Sometimes he composed several lieder on one day, particularly in July and August 1815 or for instance on October 15th - on this day alone he set eight lieder to music. It is understandable that this nourished the legend of Schubert composing his music in „trance".Schubert's dealing with the lieder tradition of the 18th century is finished in autumn 1816. Out of the strophic and the through-composed lied he created the synthesis of the „varied lied in stanzas", the type of the characteristic „Schubert lied".

The lieder of the middle creative period

The lied in stanzas becomes more and more unimportant in comparision with the through-composed lied.

In 1817, the thematic main emphasis is the motif of the death as redeemer. To this theme belong the Claudius-Lieder, Der Jüngling und der Tod (D 545) after Spaun, An den Tod (D 518) after Schubart or Memnon (D 541) after Mayrhofer.

Another lied after Schubart, the Trout (D 550), gave the theme for the Trout quintet (D 667), commissioned by Paumgartner. A break in Schubert's lieder work occurred then. Till the end of 1817 he composed little less than 300 lieder, then, in the first half of 1818, just three, even though longer ones; in the second half Schubert composed another eleven.

In 1821, the composer turned once again to Goethe's poetry - this time to the „West-Östlichen Divan". The Suleika poems appealed particularly to him. In addition to that he set the two Mignonlieder D 726 and 727 from the „Wilhelm Meister" to music.

In 1822, Schubert orientated himself again by his circle of acquaintances and friends and set Mayrhofer and Schober, Bruchmann and the friend J. C. Senn, living in exile in Tyrol, to music.

The year 1823 is worthy of note because of the reflourishing

interest in composing ballads after a longer break. With the twenty lieder

of Die schöne Müllerin (D 795) ends the middle phase in Schubert's

lieder work. In this cycle, Schubert turns once more to the lied in stanzas,

before he concerns himself almost exclusively with the varied type.

The lieder of the last creative period (1824-1828)

With the Doppelgänger (D 957/13), the last lied of the Schwanengesang, another important creative phase for history of the genre is in the offing, the phase of the so-called „declamatory" lied, that Hugo Wolf will develop only at the end of the century.

With just four lieder after Mayrhofer (D 805 to 808), the year 1824 means another break in Schubert's lieder work. It was the year of the instrumental music.

In 1825, Schubert turned again to the lied. New names appear among the poets set to music: Craigher, Pyrker and Walter Scott. He grouped the seven songs after Scott into a kind of cycle in a songbook and published them as op 52. The Ave Maria (D 839) from this book is considered to be the most famous and popular lied at all besides the Lindenbaum (D 911,2).

The poems by Scott and Schulze manifest sentiments of resignation and hopelessness. In addition, Schubert set from 1826 to the end the partly wistful poetry by J. G. Seidl to music. The composer grouped the first three lieder after this poet into one opus (No. 80).

With the four Gesänge aus „Wilhelm Meister" (D 877), without doubt

the height of the year 1825, Schubert took definitely his leave of Goethe.

After he had set for the first time three texts by Shakespeare to music

in July 1826, a longer break followed till January 1827. As he had moved

to Schober's, who had a library, Schubert had the possibility to become

acquainted with other poets.

In this last year before his death, he composed the Winterreise (D

911), made of 24 lieder and characterized by a „gloomy mood".

In the last year of Schubert's life, as he composed in rapid succession some of his greatest works - such as the string quintet D 956, the last three piano sonatas D 958 to 960 and his mass in E flat major D 950 - he composed also some of his most famous lieder. Two of them break the usual accompaniment of the pianoforte: Auf dem Strom (D 943) and Der Hirt auf dem Felsen (D 965) require a supplementary horn respectively a supplementary clarinet.

Polyphonic lieder

He composed most of the polyphonic songs for a particular occasion, at his friends' request or for a patron, of whom he expected financial support.

The trios

While the lieder duets play a minor part in Schubert's works - the duet from Goethe's „Wilhelm Meister" Nur wer die Sehnsucht kennt (D 877) should be the most famous - the trios are more important in his works. Most of the approximately 50 works were composed at the Konvikt. At times, he composed almost exclusively trios, proved by the rapid succession of the numbers in the thematic list (for example D 37-38, 43, 51, 53-58, 60-67, 69-71A). Except two exceptions, it is about trios for two tenors and one bass a cappella respectively with piano accompaniment such as for example Die Advokaten (D 37) or with guitar (Zur Namensfeier meines Vaters D 80) and about several canons for three, sometimes not specified voices. It is to be supposed that most of the early trios were for the common singing at the Konvikt. Also the trios composed from August 1815 on, such as Mailied (D 129), Puschlied (D 277), Goldener Schein (D 357) or Widerhall (D428), were composed for similar ensembles formed ad hoc in the circle of friends. When Schubert had no appropriate composition on him on the occasion of such a meeting, he was even locked up in a room to compose a new trio.The vocal quartets

Unlike in German cities or in Switzerland, where numerous choral societies had been founded since the turn of the century, there was no possibility in Vienna in Metternich's time to develop in choirs. Societies, assemblies or other groups of like-minded persons were prohibited. Nevertheless, a „new world feeling", pushing the German social music „from the indoor air of the Enlightenment into the open and wide", could not be prevented also in Vienna. Choir lieder and vocal quartets seem „ to be composed endeavoring to give a circle of young men harmonically saturated lieder under liberation from the room constraint of the piano". In 1843 the Wiener Männergesang-Verein (Viennese male-voice choral society) was founded at last.With his male quartet published in 1802 in Salzburg, Michael Haydn was the first renowned composer composing for such an ensemble. Schubert was acquainted with Haydn's male quartets. He composed more than forty works for this orchestration, about thirty of them had no instrumental accompaniment. Lieder such as Frühlingsgesang (D 709) or Lied im Freien (D 572) reveal already in the title that they are conceived for open-air performances.

Schubert composed most of his quartets for his circle of friends and acquaintances, he often sang with them. The interpreters were mostly so-called „dilettantes", hence music lovers without musical training, but who were endowed with considerable vocal qualities.

In the evening entertainment concerts of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (society of music lovers) or in the semi public concerts at the house of the Sonnleithner family, such vocal quartets were very much in vogue for a while. Then they seem to have lost gradually their fascination. In 1823, Schubert deplores in a letter to Sonnleithner „how things looked for the reception of later quartets; people have had enough".

Apart from his lieder, his male quartets helped Schubert also

to become well-known outside Vienna. Das Dörfchen (D 598),

Schlachtlied (D 912), Geist der Liebe (D 747), Die Nachtigall

(D

724) or Der Gondelfahrer (D 809) became famous and were performed

on various occasions. For Anna Fröhlich and her pupils Schubert composed

two female quartets with piano accompaniment, the 23rd psalm (D 706) and

Gott in der Natur (D 757). Like some male quartets they were probably performed

chorally.

The piano music

The sonatas

Nevertheless, he dealt intensively with the genre of the sonata. In summer 1817, he composed the piano sonatas in A minor (D 537), in A flat major (D 557), in E minor (D 566), in D flat major respectively in E flat major (D567/568) and in B major (D 575). From 1818 the sonata fragments D 608, 610, 613 and 625 are preserved. These handed down fragments end usually with the begin of the recapitulation, i.e. they end before the formative repetition of the first musical section. With that the composing and teaching process was finished for Schubert - everything else would have been only routine wasting precious time and paper.

Already these works of learning and practicing show the fundamental properties of Schubert's later great sonatas. Beethoven's works of this genre are distinguished by a motivity broken into the smallest part, a pithy rhythm and the sharp contrast of the themes, whereas Schubert's sonatas are formed by a subjective personal expressiveness aiming strongly at the sound and the atmosphere. The melody comes to the fore and the musical ideas are treated after the variative composition principle.

When Schubert thought that he had found his personal style, he published his Première Grande Sonate pour le Piano-Forte op. 42 (D 845) registered as „first" piano sonata (composed in spring 1825). As a matter of fact, he had composed already nearly twenty works of this genre till then. In August 1825, he composed the piano sonata D 850 during his journey with Vogl in Badgastein.

In the next two years, Schubert dedicated to the piano only the funeral march (D 859) for the death of the Russian czar and a heroic march (D 885) on the occasion of the coronation of the new czar Nicholas I.

One day in 1827, Spaun paid a visit to Schubert, who was just composing a sonata: „Though disturbed, he played immediately the just finished piece for me and, as I liked it very much, said: »If you like the sonata, it shall be yours, I want to make you as happy as I can«, and soon he took it to me copperplate and decided." It is about the piano sonata in G major D 894 published as Fantasy.

A few months before his death, Schubert composed the sonatas in

C minor (D 958), in A major (D 959) and in B-flat major (D 960). He made

the first sketches in spring 1828, the fair copy was finished on September

28th. Schubert entitled the pieces just „Sonata I", „Sonata II" and „Sonata

III" to characterize them as coherent group of works.

Compositions for four hands

In 1824, Schubert wrote to his friend Schwind: „I have compose a great sonata and variations for 4 hands, which met here with particular approval, but as I rather mistrust the taste of the Hungarians, I leave it to you and the Viennese to decide on this." The sonata with four movements D 812 was surnamed Grand Duo by the publisher Anton Diabelli, who published it as op 140 in 1837 and dedicated it to the pianist Clara Wieck. In 1840, Clara Wieck married Robert Schumann. When Schumann was in Vienna and saw the autographic manuscript of the work, he supposed that it was about a piano version of a symphony.

The Divertissement à l'hongroise in G minor for

piano for four hands op 54 (D 818) became also famous. Karl Freiherr von

Schönstein reports that the theme of the work records a Hungarian

song. Schubert heard during a stroll a kitchen-maid singing the tune: „We

listened to the singing for a long time, Schubert liked obviously the song,

hummed it for a long time still walking on and what do you know it appeared

in the mentioned composition for piano in the next winter." Receiver of

this piano music for four hands was Schubert's student Comtesse Caroline

Esterházy. The composer is supposed to have worshipped her secretly.

To air his affection for her, he is supposed to have set the parts so that

the hands of the two players had to touch each other now and then... In

1828, Schubert dedicated to his student one of the most beautiful compositions

of the piano literature for four hands, the Fantasy in F minor (D 940).

The impromptus

With his 6 impromptus, published in 1822, the Bohemian composer

Jan Hugo Worzischek, living in Vienna, introduced this term for the first

time as genre term for greater piano compositions. Carl Maria von Weber,

Johann Wenzel Tomaschek and Heinrich Marschner composed also impromptus

a short time later. When Schubert wanted to publish four compositions for

piano as op 90 (D 899) in 1827, the publisher Anton Diabelli proposed him

this designation. The four pieces D 935, published posthumously in 1838,

were also published as impromptus.

Dance and light music for piano

Some dances are named after the place of their composition. Schubert improvised for instance the Atzenbrugger Deutsche on the occasion of the Schubertiads of Atzenbrugg and wrote them down later. When Schubert was invited by the Pachler family in Graz in 1827, he composed the Zwölf Grazer Tänze (D 924) and the Grazer Galopp (D 925) on the occasion of a festivity at the nearby castle.

The chamber music

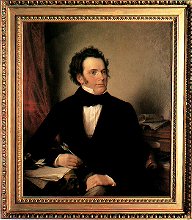

Franz Schubert

Schubert's chamber music plays an important role in his works. Fourteen complete string quartets, one piano quartet, numerous piano duets with different orchestrations, two string and two piano trios, two string quintets and one piano quintet, two octets and moreover a great number of single settings and fragments reckon among this genre.

In the 17th and 18th century, the chamber music belonged to the exquisite forms of the courtly entertainment, but at the beginning of the 19th century it became an integral part of the bourgeois culture. Particularly the string quartet became more and more in vogue at the bourgeois houses.

Also in Vienna at the Biedermeier period music was made eagerly: An anonymous author of the Viennese „Vaterländische Blätter" reports in 1811 that you would find here just a few houses „where any families would not entertain themselves with a violin quartet every evening" instead of taking „the playing cards once ruling so despotically".

Schubert's early string quartets were composed for the family „quartet exercises" - but from a musical and technical point of view they surpassed by far the level of the usual music-making in the home at that time. Particularly demanding is the violoncello voice played by Schubert's father.

From 1815 to 1824, Schubert composed not much chamber music and no string quartets at all. In 1816/17, he composed some duets for violin and piano for his brother Ferdinand as well as the two string trios D 471 and D 581. In 1819 he composed the famous Trout quintet (D 667) for the violoncellist Sylvester Paumgartner, in 1821 the so-called Arpeggio sonata (D 821).

Only in 1824, he devoted himself again to the instrumental music. With the chamber music he wanted to „work his way to the great symphony" after having failed with his operas. At the end of February, he composed after a longer period a string quartet, the quartet in A minor (D 804) which became known under the name of Rosamunde-Quartett. This month he composed also the octet in F major (D 803) - probably a commissioned work for Count Ferdinand von Troyer, who is supposed to have played the clarinet himself on the occasion of the performance in spring 1924.

In March 1824, Schubert composed the famous string quartet in D minor (D 810) surnamed Der Tod und das Mädchen after his lied of the same title about the text by Matthias Claudius (D 531). The variation theme of the second string quartet movement is arranged after the melody of the lied. This quartet is regarded as Schubert's most gloomy instrumental work.

The string quartet in G major (D 887), composed in 1827, is his last work of this genre. Like Beethoven's last quartets, it goes beyond the stylistic scope of the classical string quartet.

From the end of 1827 to the beginning of 1828, Schubert composed the two piano duets in B-flat major (D 898) and in E flat major (D 929) for piano, violin and violoncello accompaniment. He sent the piano trio in E flat major to the publisher Probst. He dedicated the work to „those who enjoy it" and „looked forward longingly" to the publication. On October 2nd 1828, six weeks before his death, he inquired urgently again of the publisher about „when will the trio be published at last? I am looking forward longingly to its publication". On his own showing, Probst has been detained abroad, but promised to speed the matter up. In vain - Schubert did not live to see the publication.

Schubert composed two other pieces for small accompaniment, the Rondo brillant (D 895), with which he complied with the wishes of that time for virtuoso pieces, and the fantasy for violin and piano in C major (D 934) probably for the violinist J. Slawjk. The theme of the variation movement in the fantasy has its origin in the lied Sei mir gegrüßt (D 741).

Schubert's highly important last chamber music work, the string

quintet in C major (D 956), was probably composed shortly after the Mass

in E flat major (D 950) in August or September 1828. He offered it in vain

to the music publisher Probst in Leipzig and so, one of the most beautiful

works of Occidental music was published only years after Schubert's death.