|

Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune

Images pour orchestre Printemps The Cleveland Orchestra

Deutsche Grammophon 435 766-2

|

When Pierre Boulez signed an exclusive contract with Deutsche Grammophon at the start of the 1990s, the company offered him carte blanche – meaning, he could record anything he wished, and with anyone he chose. He stuck with re-recording most of his repertoire, and this Debussy collection was the first to surface.

For me, Boulez (right) is a Debussy-conductor par excellence: he is totally

at home with his compatriot’s musical language and inimitable sound-world,

and, like Debussy, does not settle for anything less than pure, unadulterated

art. That does not mean, however, that what we get here is perfect; or

cannot be improved upon. I’ve come across better performances (both ‘live’

and on record) of each of these works, but in all honest truth, nobody

understands Debussy like Boulez does. There’s just this something ‘extra’

that I find in Boulez’s Debussy that I cannot detect in someone else’s:

it’s unidentifiable – perhaps it’s the ‘french-ness’, the poetry, the colour

that is so utterly Debussyian; and these are the components of a Boulez-performance,

the like of which you will hear in this collection.

For me, Boulez (right) is a Debussy-conductor par excellence: he is totally

at home with his compatriot’s musical language and inimitable sound-world,

and, like Debussy, does not settle for anything less than pure, unadulterated

art. That does not mean, however, that what we get here is perfect; or

cannot be improved upon. I’ve come across better performances (both ‘live’

and on record) of each of these works, but in all honest truth, nobody

understands Debussy like Boulez does. There’s just this something ‘extra’

that I find in Boulez’s Debussy that I cannot detect in someone else’s:

it’s unidentifiable – perhaps it’s the ‘french-ness’, the poetry, the colour

that is so utterly Debussyian; and these are the components of a Boulez-performance,

the like of which you will hear in this collection.

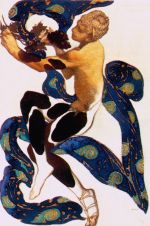

The Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun) was completed in 1894, and successfully premièred that same year to an approving but bewildered audience – puzzled, no less, by the obvious formless-ness of the work. It was to be performed again in a staged production choreographed and danced by Nijinsky (costume depicted below) for the "Ballet Russes", this time to a riotous furore.

The Prélude, however, was a breakthrough in musical composition:

with its inception, music was never to be the same again. In it, Debussy

abandoned the traditional harmonic, thematic, structural and rhythmical

rules which had governed musical composition; and achieved, in his own

words, "... music [that is] truly freed from motifs, or constructed on

only one continuing motif which nothing interrupts, and which never goes

back on itself."

The Prélude, however, was a breakthrough in musical composition:

with its inception, music was never to be the same again. In it, Debussy

abandoned the traditional harmonic, thematic, structural and rhythmical

rules which had governed musical composition; and achieved, in his own

words, "... music [that is] truly freed from motifs, or constructed on

only one continuing motif which nothing interrupts, and which never goes

back on itself."

Despite frequent suggestions of particular keys, the work never really settles in any; and does not belong to one. Debussy had intended not to let the music rely on particular tonal centres, but sought through an attenuated tonality "... a mode that tries to contain all the nuances [of different keys]". Pierre Boulez firmly believes that if modern music had had a definite beginning, it must have been the opening bars of the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. The work’s source of inspiration came from a poem by the French poet, Stéphane Mallarmé, who was a friend of the composer and an admirer of his music...

| Ces nymphes, je les veux

perpétuer.

Assoupi de sommeils touffus. En maint rameau subtil, qui, demeuré les vrais Bois mêmes, prouve, hélas! que bien seul je m'offrais Pour triomphe la faute idéale de roses. Réfléchissons ... |

I desire to perpetuate

these nymphs.

So bright their light rosy flesh

that it hovers in the air drowsy with tufted slumbers.

|

Just listen to how Boulez builds up the climax in the middle section (marked

"Même mouvt et très soutenu" in the score) to the only fortissimo

in the work, and how carefully he urges the orchestra not to overplay,

but to keep at establishing the timbre they have effected since the start.

And don’t miss, too, the shimmering string-tremolos at the coda(?) section

(return of the original theme on flute and oboe), beautifully rendering

the dreamy faun’s return to his mid-afternoon rêverie.

Just listen to how Boulez builds up the climax in the middle section (marked

"Même mouvt et très soutenu" in the score) to the only fortissimo

in the work, and how carefully he urges the orchestra not to overplay,

but to keep at establishing the timbre they have effected since the start.

And don’t miss, too, the shimmering string-tremolos at the coda(?) section

(return of the original theme on flute and oboe), beautifully rendering

the dreamy faun’s return to his mid-afternoon rêverie.

I think one important characteristic of Boulez’s Debussy is his understanding of the music’s affinity with the French language: the composer, by the way, intended his music to sound every bit like his mother-tongue. Boulez, being also French, is thus purely instinctive with regards to the various "French" inflections that underline Debussy’s scores.

Images is a symphonic tryptich which seeks to express and embody the distinct characters of three different countries: England, Spain and France. In writing Images, Debussy said he was seeking "... an effect of reality; music [that is] made up of colours and rhythms", but with a greater variety of textures and a wider lyrical expansion than in any of his previous works.

The first movement, Gigues, a musical representation of the composer’s biased view of England, has as its central theme the Northumberland folk-song, The Keel Row. Here, Boulez manages to keep the intricacies of ensemble-playing together, yet at the same time crafts a sound which is altogether warm and homogeneous: the characteristic Boulez-Debussy sound I often emphasize. A slight problem lies with the recording, perhaps, which places certain sections forward and relegating others to the rear; thus sacrificing a considerable amount of inner-detail in isolated parts of the score.

The excitement is very much contained in Iberia, the second movement which is in itself divided into three sections. In the first, Par les rues et par les chemins ("In the Highways and Byways"), Boulez exudes more continental "gentleman-ness" than southern "Spanish" fervour: try Pierre Monteux’s definitive Philips recording (442 595-2 "The Early Years" Series) and you’ll hear all the glitter and bustle of the streets, and the fervour and langour of the characteristic Spanish dance rhythms are vividly depicted.

My earlier grouse about the recording-quality remains. Boulez’s downplayed emotions work better in the second section Les Parfums de la nuit ("The Perfumes of the Night"), where he successfully evokes an atmosphere of perfume mists shrowding a dimly-lit alleyway. However, I would have preferred more effeminacy; and those slinky string-glissandos at the beginning could have been better.

The final section Le matin d’un jour de fête (Morning of a

Festive Holiday) comes-off better and is given a characterful performance.

Here, Boulez sustains tension well and the orchestra plays superbly.

The final section Le matin d’un jour de fête (Morning of a

Festive Holiday) comes-off better and is given a characterful performance.

Here, Boulez sustains tension well and the orchestra plays superbly.

Much the same can be said of the performance here of Printemps ,one of Debussy’s earlier works which show already more than a glimpse of the future composer of such works as those two above. It is a symphonic suite divided into two movements which attempts to express the slow, laborious birth of beings and things in nature, then mounting florescence, and finally a burst of joy at being reborn to a new life". It is Boulez’s characteristic "frenchness" which very much defines his interpretation; and listeners familiar with Debussy’s music cannot but admit that only he (Boulez) is capable of exuding such lovely sounds from an orchestra to play what the composer only intended as "music that pleases the ear and caresses it". Throughout, careful attention is paid to phrasing and homogeneity of sound; and the structure of the work also becomes apparent.

For other recommendations

of the Prélude, try the abovementioned Karajan performance;

or the one by Michael Tilson Thomas and the London Symphony Orchestra (Sony

SK48231). Images cannot be bettered by Pierre Monteux’s Philips

recording (442 595-2); but is also well-served by Simon Rattle (EMI 7 49947-2)

and Esa-Pekka Salonen (Sony SK62599). But, like I said earlier, Boulez’s

Debussy is special and should be heard.

![]()