| [naar

inhoudsoverzicht Strauss-dynastie]

[naar

literatuurlijst]

inhoud:

|

JOSEPH & EDUARD STRAUß

Josef Strauß (1827-1870)

The career

Josef Strauss began his technical studies in 1842 at the Viennese polytechnic.

From 1846 on, he worked as construction draftsman in addition to his studies.

After becoming a diploma'd engineer, he worked in different branches: among

other things he constructed a road sweeper.

During the revolution of 1848, he was in the Academic Legion for a

short time, but left the

insurgents soon, hid the uniform and the weapon and retired into the

monastery of the hospitallers, where his family lived during the fights.

During his technical studies, he concerned himself also with music,

but he refused to become a professional musician. But after the strenuous

winter season, when his brother Johann contracted a serious disease and

the physicians ordered him a rest of six months, the inexperienced Josef

had to take over the direction of the Strauss band - just for a short time,

as they said. The temporary collaboration became a commitment for life.

Three years later, he was compelled to give up his technical career in

favor of the music and the family "show business".

He performed for the first time with the Strauss band on July 23rd 1853

at "Sperl" and was very successful. As Josef was neither experienced in

conducting nor a versed violinist able to conduct the orchestra with the

instrument in his hands, he took violin lessons again and continued also

his studies of musical theory. Although he had not the strong personal

magnetism of his brother, he became also as conductor soon popular with

the public.

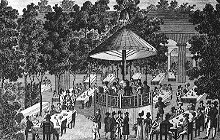

"Zum Sperl" - garden

But when they both performed at the same event, Josef was in the famous

brother's shadow. Therefore, he tried to distinguish himself as composer

as well as conductor. Already in his first "musical summer" in 1853, he

threw the usual programming of the Strauss concerts, composed of dances

and popular opera themes, overboard in conducting also Liszt's symphonic

poem "Mazeppa" and scenes from Wagner's "Lohengrin". Later, he incorporated

other works of the new German school and different compositions of the

classicism and the Romanticism in therepertoire.

His duties as conductor grew in the course of time. In 1856, he gave

up his career as engineer for good, when he had to act for Johann for six

months during his sojourn in Russia. In 1862, the elder brother sent him

even to Russia to the summer concerts in Pavlovsk, since he went back to

Vienna "for medical reasons" (but in actual fact because of his marriage).

In 1863, Johann became Hofballmusikdirektor and his performances were restricted:

Josef and Eduard assumed the other duties as conductors. But the collaboration

of the two brothers free from conflicts. Josef was responsible for most

of the events.

The great professional stress contributed probably to the aggravation

of his uncleared congenital disease. Syncopal attacks and collapses became

more frequent without the physicians being able to detect the cause. Nevertheless,

new plans were made again and again. For summer 1870, they scheduled a

great concert tour to Warsaw - it became his last journey.

On the occasion of the inaugural ceremonies of the new Musikverein building

in January 1870, all three brothers played and each one contributed a new

composition. In March, they performed again at the Musikverein and

this was their last joint performance.

Grave Josef Strauß

at the Wiener Zentralfriedhof

In April 1870, Josef set out for Warsaw, where several concerts were

timed at the establishment "Schweizertal". But the journey started with

a fiasco: The books of music and the instruments arrived too late and the

band was incomplete. Finally, they started with the concerts two weeks

behind the schedule. The agitation told heavily on Josef: During a concert,

he had once more a heavy syncope with paralytic symptoms and speech disorders.

The patient was transported to Vienna where he died on July 22nd. Three

days later, he was buried close to his mother at the St. Marxer Friedhof

in deep sympathy of the people and later he was laid to rest at the Zentralfriedhof

(Ehrengräber-Gruppe 32 A, No. 44).

The works

Within 17 years of musical work, Josef Strauss left to us 283 printed works:

mainly dances

(waltzes, polkas, polka-mazurkas, quadrilles, marches and ländler),

but also lieder and two

plays, an operetta after his own libretto and a tragedy.

As composer, he wanted to take his own way: His symphonic concert waltzes

were orientated by Liszt's and Wagner's tone style and had not much in

common with the popular light music of the Strauss family. But these works

kept unpublished and are missing as well as the other autographs of the

composer.

Some dances (for instance the "Pizzikato-Polka") were composed in "teamwork"

with Johann and Eduard.

The adaptations for the Strauss band are of particular importance in

the works of Josef Strauss. Josef was the most talented composer among

the three brothers at all. Johann saw the talent of his brother and he

is supposed to have said several times: "Pepi is more talented, I am more

popular."

Josef's tone style has poetic, romantic melancholic characteristics

and is influenced by Schubert and Chopin. The freely composed waltz introductions

as well as some polka-mazurkas show stylistic characteristics of the new

German school.

Private things

On June 8th 1857, Josef Strauss married Caroline Pruckmayer (1831-1900)

at the church St.Johann in Leopoldstadt. The couple lived with the extended

family at the Hirschenhaus in Leopoldstadt. In 1858, the only child was

born, Karolina Anna (deceased 1919).

After Josef's death, Caroline moved to Karmelitergasse 9. In 1893 she

moved to Czermakgasse 16 in Währing. She died on November 22nd 1900

in Hainfeld.

Josef's musical estate came first to Johann and Eduard took it over

a few years later. Today, we have to puzzle about the destiny of the manuscripts,

because not an autograph, not even sketches are transmitted by Josef Strauss,

just his printed works.

Eduard Strauß (1835-1916)

The career

Eduard Strauss graduated from the Viennese academic gymnasium and aspired

to a diplomaticcareer, but his mother opposed this plan. He allowed himself

to be persuaded to study music, took theory, piano and violin lessons and

learned the fashionable instrument harp.

In carnival 1861, he made his debut as conductor: In a "Monstre-Ball"

at the Sofien-Säle (Wien 3., Marxergasse 7) each brother was conducting

a band.

Eduard contributed also a composition announced to be on the safe side

in Josef's name. In the next year, he conducted the Strauss orchestra for

the first time in an own concert at the Diana-Bad.

The formerly Diana-Bad

In spite of the popularity of his brothers, Eduard succeeded in winning

the public's favor. Early in 1865, when Johann and Josef contracted a serious

disease, Eduard filled the majority of the carnival performances. He had

even to act for Johann in the summer concerts in Pavlovsk in Russia. He

was successful there as conductor, but he got involved in differences,

which ended in the fact that no more Strauss was invited to Pavlovsk.

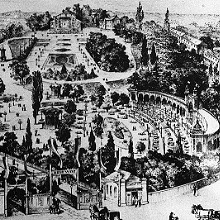

The "Neue Welt"

After Josef Strauss death in June 1870, Eduard was the only conductor

of the band. He performed with the orchestra on Thursday and Sunday at

the "Neue Welt", on Tuesday and Friday at the garden of Weghubers Caféhaus

in the Innere Stadt (Wien 1., Museumstraße), on Wednesday at the

Hotel Victoria, on Saturday at the garden of the Blumensäle and later

also at the Volksgarten.

Through many years he made the ball music in the carnival for four establishments:

On Saturdays in the carnival he played first at Dommayer, then at Schwenders

Colosseum, at the Blumensäle and finally at the Sofien-Säle.

For this ten-hour mammoth action, that he conducted himself only in part

though, he extended his band up to 120 to 130 musicians.

His "Concerts populaires" at the great hall of the Musikverein were

a novelty. Half the program of this Sunday's event, where the audience

sat at tables and drinks were served, was composed of old and new works

of the so-called "classical" music, the other half of music of the Straussfamily.

Strauss toured through Germany (1885, 1889, 1896), England (1885, 1895

and 1897), St.Petersburg (1894) and America and Canada (1890 and 1901).

On the second tour in America, Strauss went to 81 cities and gave 106

concerts. This last forced tour led to discords between him and the musicians,

so that he dissolved the band

after the home-coming in February 1901 - after about 75 years of contract

with the Strauss family.

The works

Eduard Strauss left 280 published works, more than the third part are polkas

and gallopades. His compositions are skilled solid, but they lack the personal

note. In the invention they are hardly more than a colorless reflection

of the music of his brother Johann.

Family background and dwellings

In January 1863, Eduard Strauss married Maria Klenckhart, the daughter

of an owner of a café in Leopoldstadt living vis-à-vis the

"Sperl". The couple lived first at the Hirschenhaus with the extended family,

where the two sons Johann (1866-1939) and Josef (1868-1940) were born.

In 1886, Eduard was the last Strauss to leave the Hirschenhaus with his

family and moved into a new house in the Innere Stadt (Wien 1., Reichsratstraße

9), where he lived till death.

The elder son studied law a few semesters and worked then as reviser

in the Imperial and Royal ministry of Culture and Education. About 1900,

he gave up this post in favor of the profession of musician. A year later,

he succeeded his father in the direction of the court ball music, which

he occupied until 1905. In 1906, he applied for the title of Hofballmusikdirektor

(court ball music director), but it was not conferred on him, since he

was heavily indebted. In 1907, he moved toBerlin with his family.

The financial calamities of the son had led to discords between Eduard

Strauss and his wife: through years, she had helped the son at the expense

of the family fortune and the encumberedcommon house was finally put up

for compulsory auction.

The "last Strauss"

Not only an important chapter of Austrian history of music ends with

Eduard Strauss, but his death means also the end of a well-organized and

successful family business, a

"show empire", which was keen on influence and profit. The competition

of the rivals among one another contributed a lot to its boom, but brought

naturally discords into the family relations.

Eduard's relationship with his eldest brother was often strained. Johann

remembered him neither in his will he made before his journey to America

in 1872, nor in his last will.

On the occasion of the world's fair in 1873, Johann ousted him rigorously

and he was not

allowed to perform at the exhibition garden. Eduard, in his turn, was

not present at Johann's funeral, in his "memoirs" he explained incorrectly

that he was traveling. This in 1906 written autobiography contains no details

about the relations to his brothers, but because of its often distant and

critical manner there is reason to suppose that he felt less favored in

comparison with them. Probably there were such feelings at work, when Eduard

burned up the note archives of the Strauss band in 1907, according to an

arrangement with Josef of the year 1869. The material is said to have been

so extensive that the occurrence lasted hours - the most valuable documents

were irretrievably destroyed thereon.

The last years of his life, Eduard Strauss lived in seclusion in his

apartment at the Reichsratstraße. On December 28th 1916, he died

of old age. At his own request, he was laid to rest in the uniform of the

Hofballmusikdirektor at the Zentralfriedhof. His tomb is in the Ehrengräber-Gruppe

32 A, No. 42.

Monument Eduard Strauß

at the Wiener Zentralfriedhof

Without the work of Eduard Strauss, the Viennese dance music would have

been forgotten already a long time before the turn of the century.

In a time, when Carl Millöcker, Johann Strauss and Carl Michael

Ziehrer devoted themselves to the operetta, when the military march dominated

in the dance music, the cabaret and working class songs appeared, the last

representative of the second Strauss generation succeeded in keeping

the Viennese waltz alive for some time.

|