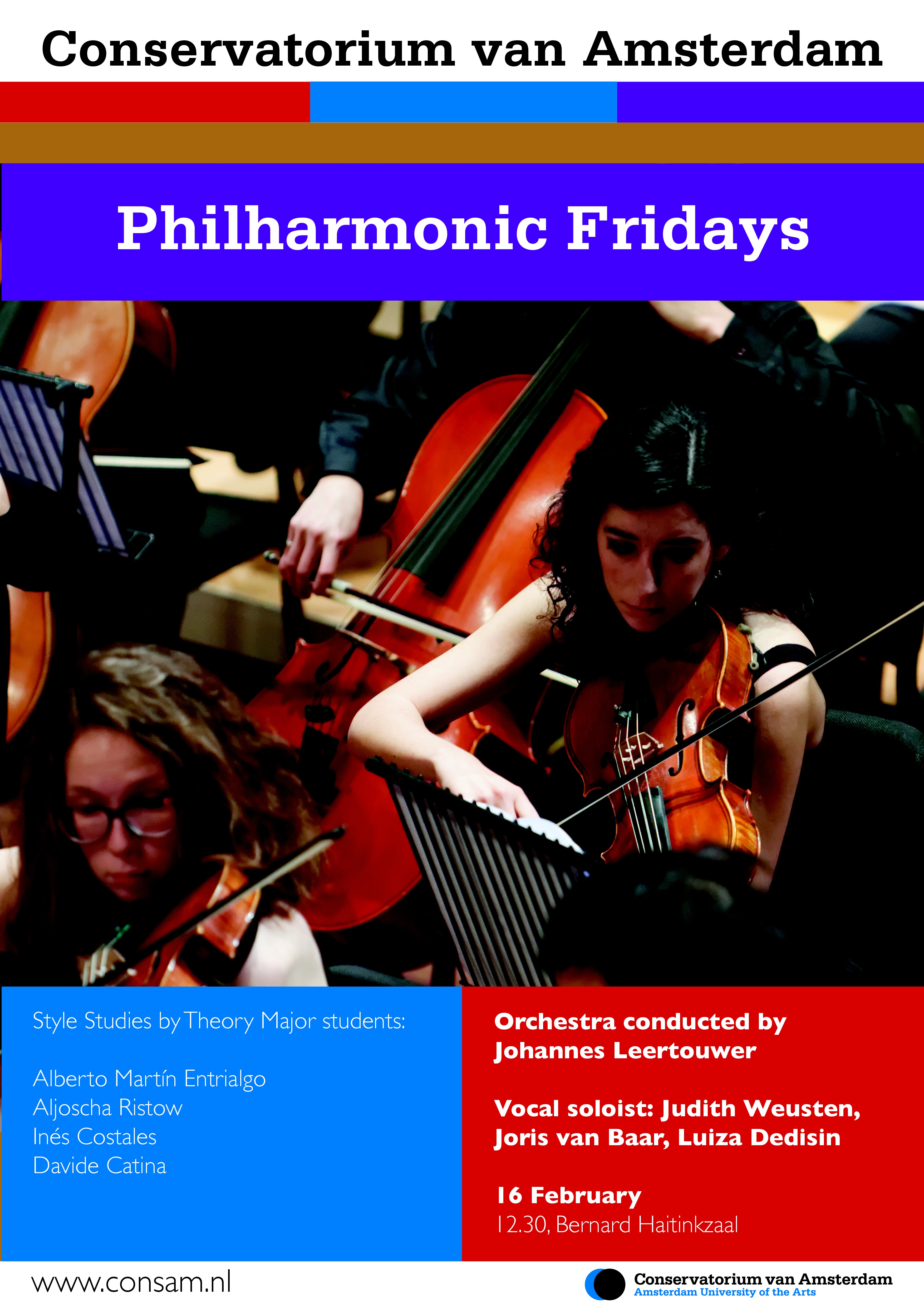

Philharmonic Fridays in collaboration with the Music Theory Major division:Performance of four Symphonic

Style Studies of Theory Major students

|

In the Philharmonic Fridays

concert on February 16, 2018 four style studies (or:

style compositions) will be performed. A style

study is a composition based on imitation or adaptation

of preceding pieces, or more in general: It is a

composition purposely using a specific style as a

framework, inspiration, or point of departure. To a

certain extent this is nothing new: to imitate, adapt

and change the style of immediate predecessors has been

common practice for centuries, and we can find many

works in which composers take works by others as a point

of departure.

The most important difference between such past practices and the works to be presented in the concert as style studies is that these pieces are not based on music of today, last year or even of the 20th century, but on music written in a more distant past. In this way we hope to contribute to a recovery of past, and largely lost composition traditions, practices, techniques and attitudes - the past being: The time before ca. 1930.

Since some years the Music Theory

major department is encouraging students to produce

style compositions - as a continuation of writing

courses like harmony and counterpoint. In the past the

resulting pieces were only performed during final exams,

but since 2015 public concerts in the Conservatory are

organized, in which chamber music or symphonic

compositions are performed. The Philharmonic Fridays

concert of February 16, 2018 is the second time that

works for symphony orchestra are performed. The

stylistic focus of the works in this concert is about

the second half of the 19th century.

For further information (for instance an introductory video), and video recordings of previous concerts, you can have a look at our youtube channel Style Composition and our facebook page.

| Alberto Martín Entrialgo | Orchestration

and Arrangement of: Isaac

Albéniz, Launcelot: Overture and Duet between

Morgan and Mordred (first act) Words by Francis Money Coutts Judith Weusten, Soprano (Morgan) |

| Aljoscha

Ristow |

Overture: Ariadne and Theseus |

|

Inés

Costales |

Nuit d´eté Text by Paul Bourget |

|

Claude Debussy / Inés Costales |

De rêve... - orchestration

by Inés Costales Text by Claude Debussy Luisa Dedizin, Soprano |

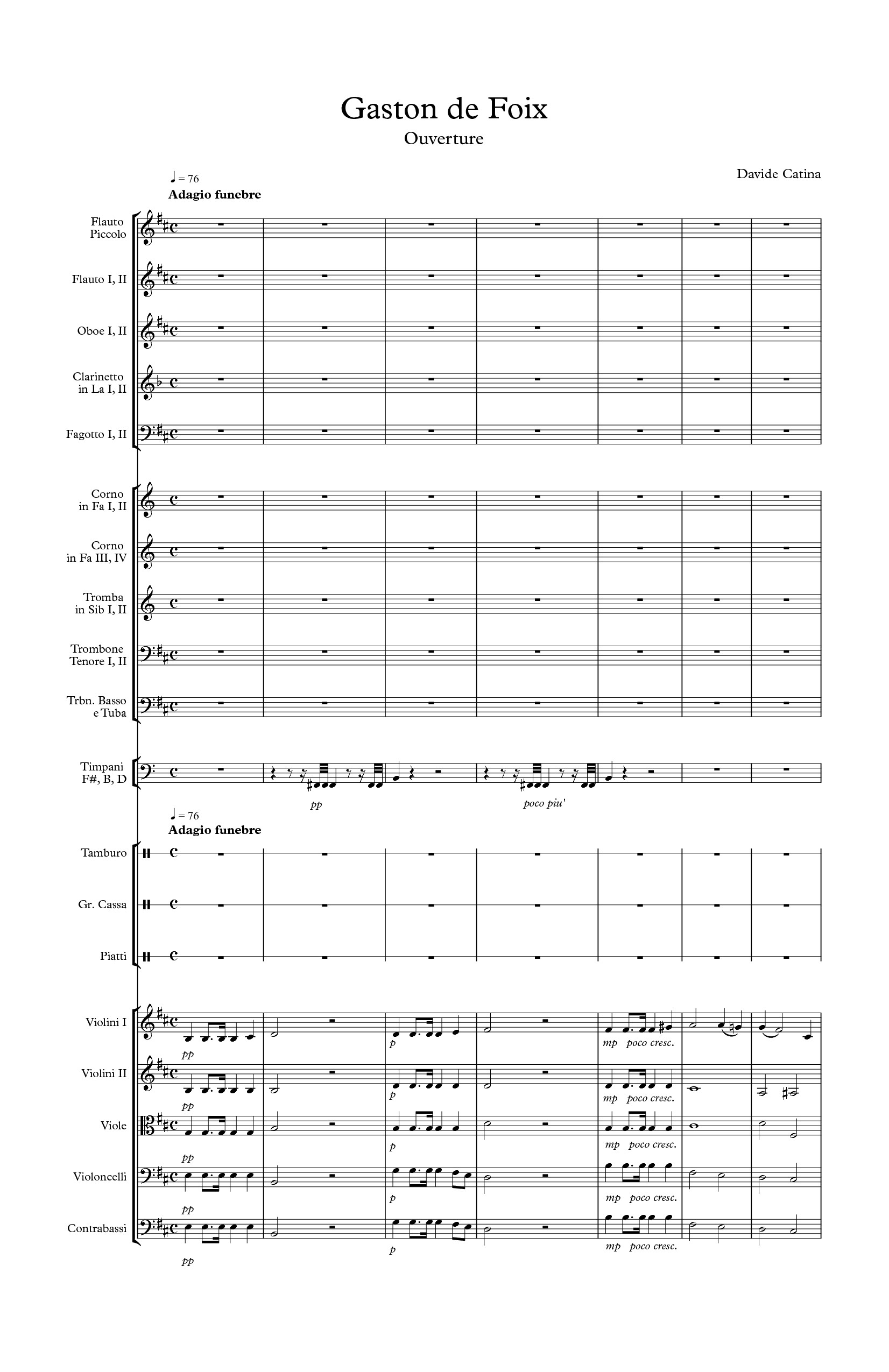

| Davide Catina | Overture: Gaston de Foix |

conducted by Johannes Leertouwer

| vocal

soloists: |

Judith

Weusten, Soprano Joris van Baar, Baritone Luisa Dedizin, Soprano |

| flute |

Agnese Lecchi Marta Vilaça |

| flute/piccolo |

Alexandre

Tkaboca |

| oboe |

Maripepa

Contreras Ella Botter |

| english horn |

Charlotte

Salter |

| clarinet |

Ana Barradas

Prazeres Jara van Dam |

| bass clarinet |

Jarred Mattes |

| bassoon |

Diego

Fernandez Lily Simpson |

| contrabassoon |

Marco Couceiro

Gonçalves |

| horn |

Stefan

Danifeld Rinske van Oosterhout Rebecca Climent Lucas Jansen |

| trumpet |

Denys Holovin Piotr Majoor |

| trombone |

Eva Schiffler Augustinas Alisauskas Adrian Gryciuk |

| tuba |

Andres Alcaraz

Lopez |

| timpani |

Lola Mlacnik |

| percussion |

Martijn Boom Sekou van Heusden Bence Csepeli |

| harp |

Juan Blanco Lisa de Bruyker |

| violin 1 |

Matthijs van

der Wel Lisette Carlebur Anna Cikste Carlo Allegri Francisca de Portugal Josefina Ribeiro Alcaide Fernandes Haejin Park Filipe Farinha Fernandes Emil Peltola Daniel Perzhan |

| violin 2 |

Nikita Kuts Stella Zake Lucas Bernardo da Silva Vanya Dolav Elisa Dijkstra Karina Sosnowska Zuzanna Skowronska Lisanne Clignett |

| viola |

Hessel

Moeselaar Martin Moriarty Floris Faber Rita Pinto Proença Audinga Musteikytė Maria Helen Körner Sergio Montero del Pozo |

| violoncello |

Patrick Karten Tom Feltgen Francisco López Serrano Xenia Watson Anna Sophie Reisener Adriana Mendez |

| double bass |

Jordi Carrasco

Hjelm Benjamin de Boer Ella Stenstedt Claudia Velez Ruiz |

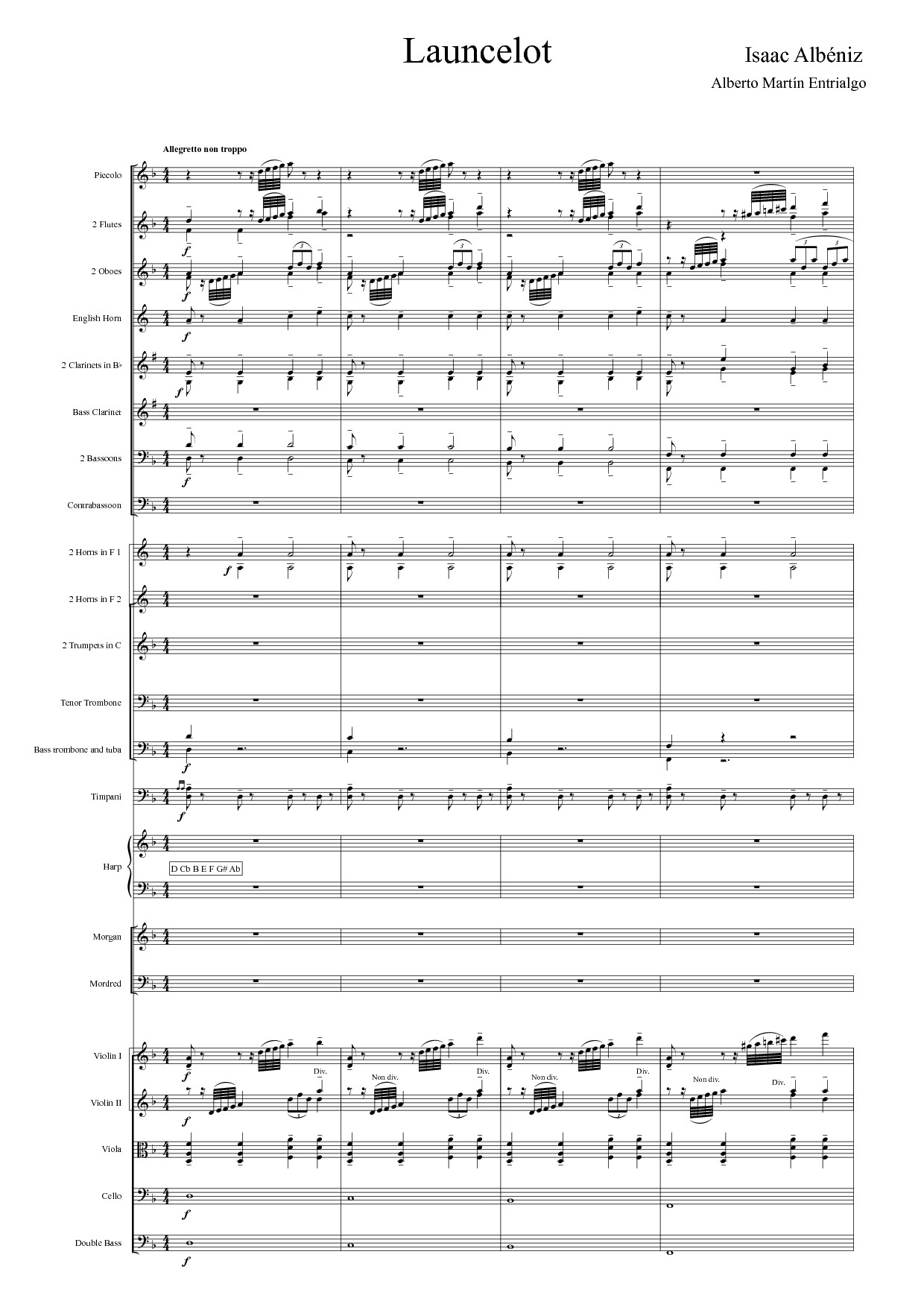

Launcelot: Overture and Duet between Morgan and Mordred (first act)

Music by Isaac Albéniz

Words by Francis Money Coutts

Orchestration

and Arrangement by Alberto Martín Entrialgo

Historical context

Around 1893 Francis Money-Coutts,

a wealthy English banker who was also a poet and writer

educated at Cambridge, proposed to Isaac Albéniz a

collaboration through which the Spanish composer would

set Coutts’s poetry to music. The products of this

fruitful association were numerous songs and stage

works, including the King Arthur trilogy, which

consisted of the operas Merlin, Launcelot, and

Guenevere. Coutts based his libretto on the

fifteenth-century Arthurian romance entitled (using

French) Le Morte d’Arthur by the English author

Sir Thomas Malory. The three libretti were published in

1897, but Albéniz only completed and published Merlin;

he also started (and perhaps even finished) Launcelot,

but Guenevere never became more than a

project.

Various manuscripts of the second

act of Launcelot are preserved, as well as the

proofs of the first act of the vocal score (by

Mutuelle). The score was never published, and the

orchestration of the first act is missing. The existence

of proofs of the first act could indicate that Albéniz

completed the opera, although no evidence supports this

claim. Given that neither the overture nor the duet has

formal closure, I composed an ending for the occasion.

Background of the Arthurian legend as conceived by Malory and Coutts

King Uther is in love with

Gorlois’s wife, Igraine. Merlin casts a spell on Igraine

so that Uther can spend at least one passionate night

with her. When Gorlois finds out, he confronts Uther,

and the duel results in Gorlois´s death. The fruit of

Uther’s and Igraine’s love affair is Arthur, on whom

Morgan, the legitimate daughter of Igraine and Gorlois,

swears revenge.

In Merlin, king Uther

dies without a legitimate heir. Morgan claims the throne

for her son Mordred; simultaneously, the archbishop of

Canterbury reveals that he has received a divine

message: the knight who takes the sword (Excalibur) out

of the stone will be crowned king of England. Arthur, to

the astonishment of the crowd, is the only one who

accomplishes this task, and is thereby proclaimed King

of England. The opera’s dramatic action mainly relies on

Morgan’s attempts to overthrow Arthur and replace him

with Mordred, an end for which she will deploy all means

at her disposal: by conspiring and colluding with anyone

she sees fit.

Morgan’s desire to destroy Arthur

continues in Launcelot. In the duet performed

today, Morgan and Mordred express their discomfort with

the king and announce their plans to overthrow him.

Arthur has married Guenevere, but Morgan discovers that

the Queen is in love with the knight Launcelot, and that

her love is reciprocated. Morgan pretends to use their

mutual love to destroy the king, so that her son,

Mordred, could finally seize power:

| Lo! When the

kingdom is riven. Cleft by a false women’s

shame, then to my son shall be given England, her freedom and fame! |

But Launcelot is a knight in His Majesty’s service, and

the King orders him to seek the Holy Grail. But

Guenevere tries to convince Launcelot to stay with her.

He is thus trapped between his duty as a knight and his

love for Guenevere.

|

| Dante

Gabriel Rosetti (1828 - 1882): Sir Launcelot in

the Queen's Chamber |

| What’s a style study? |

| Program |

| Members of the Orchestra |

| Alberto

Martín Entrialgo/ Albeniz: Launcelot, Overture and Duet |

| Aljoscha Ristow: Overture: Ariadne und Theseus |

| Inés Costales /

Debussy: Nuit d´eté De rêve... |

| Davide Catina: Overture: Gaston de Foix |

| [ back to top ] |

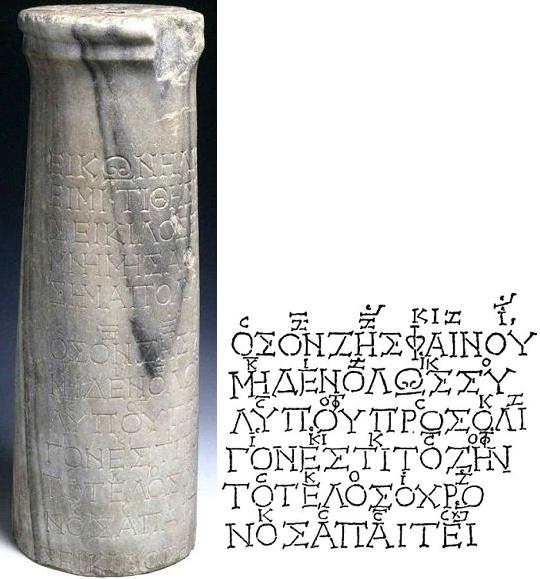

Overture:

Ariadne and Theseus

Ariadne and Theseus is a concert overture in Romantic style, and programmatically related to the Greek myth of the same name. The work is mainly influenced by the composers Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Robert Schumann, Johannes Brahms and Hector Berlioz, who may be regarded as a countercurrent to the so-called New German School of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt.

Regarding the style, this overture could be dated back to the 1880s. That would also go along with the contained melodic references to the Song of Seikilos, one of the oldest surviving compositions from ancient Greece, which was discovered in 1883 on a historic tombstone. The conflict between the ancient modality of the song and Romantic tonality is intended to express a gleam of hope within the otherwise very tragic narrative of the myth.

| As long as

you live, shine Grieve you not at all Life is of brief duration Time demands its end. Seikilos [of] Euterpe, 200 BCE – 100 CE |

|

The song appears for the first time in the slow

introduction of the overture, which refers to a very

sorrowful situation for the citizens of Athens:

According to the myth, King Aegeus of Athens had to send

seven young men and seven young women every nine years

as a sacrifice to the Minotaur, a half-animal creature

living in the complex labyrinth under King Minos’s royal

palace in Crete. Not before the tribute was due for the

third time King Aegeus’s son Theseus volunteered to be

one of the sacrifices, and planned to relieve Athens of

this burden by killing the Minotaur.

When Theseus arrived in Crete, he met Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos, and they fell in love. She was the one who gave Theseus the well-known Ariadne’s thread that helped him find his way out of the labyrinth after successfully killing the Minotaur. The unrolling of the thread, as well as the complexity of the labyrinth, are musically realised in the two themes of the overture, as they constantly lead away from the tonal center - thereby delaying the finding of an end. In the overture the heroic spirit of Theseus’s victory against the Minotaur is finally represented by the glorious reappearance of the Song of Seikilos halfway the recapitulation.

However, in the myth the joyfulness did not last very long. On the way back to Athens, Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island Naxos. The reasons for this infamous act are not entirely clear, since different versions of the story exist. To make things worse, Theseus forgot to hoist white sails as a sign of victory when approaching Athens, as agreed before. Hence, when King Aegeus saw his son’s ship arriving in Athens with black sails, he believed that Theseus had died when fighting the Minotaur. As a consequence, he threw himself down from a rock and deceased in the sea, which is therefore still known as the Aegaean Sea.

|

| Niccolo Bambini (1651–1736): Arianna e Teseo |

| What’s a style study? |

| Program |

| Members of the Orchestra |

| Alberto Martín

Entrialgo/ Albeniz: Launcelot, Overture and Duet |

| Aljoscha Ristow: Overture: Ariadne und Theseus |

| Inés Costales /

Debussy: Nuit d´eté De rêve... |

| Davide Catina: Overture: Gaston de Foix |

| [ back to top ] |

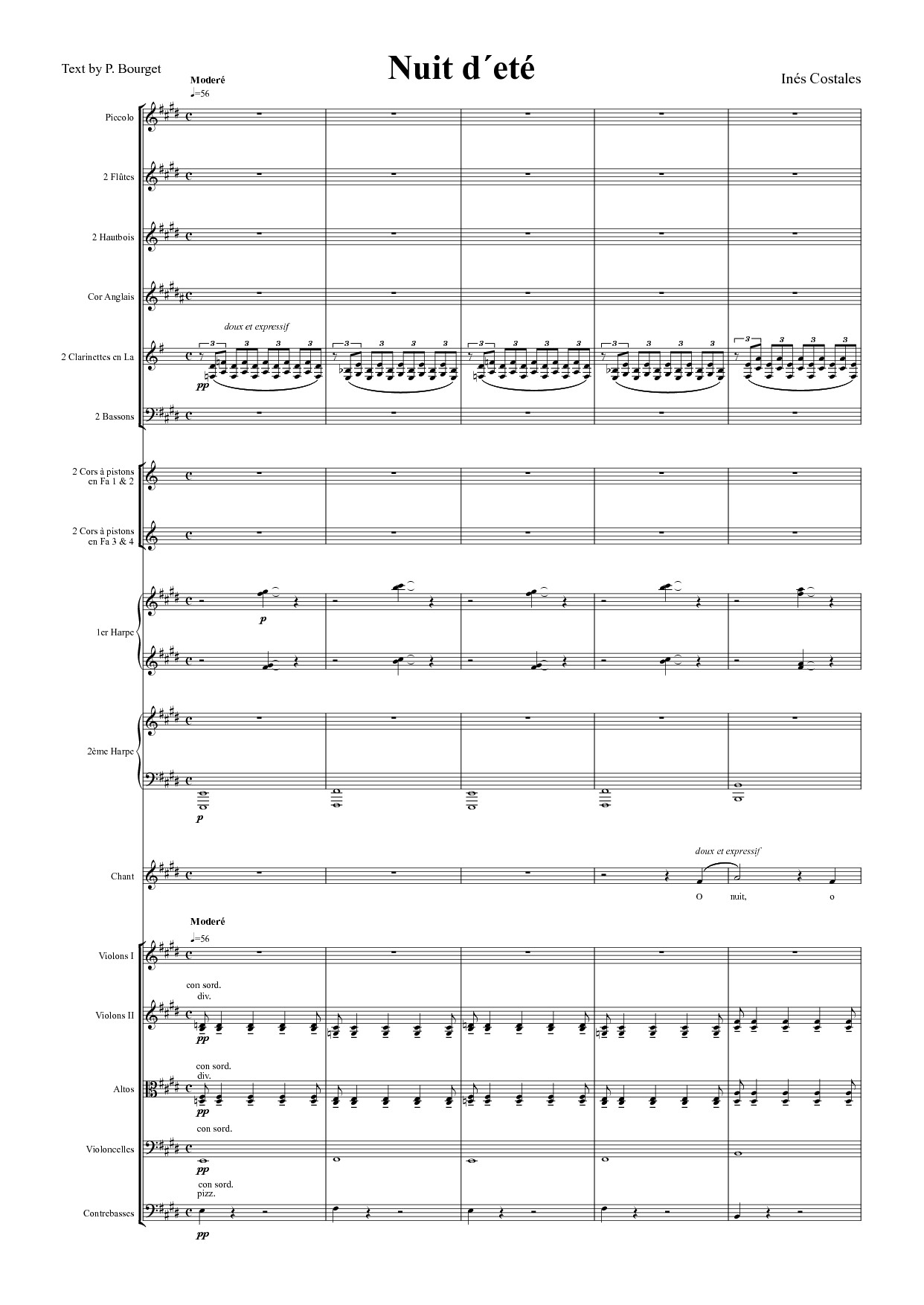

|

Original version of De

rêve… as published in

Entretiens Politiques et Littéraires, December 1892 |

Text by Paul

Bourget; music by Inés Costales

De rêve...

Music and

text by Claude Debussy; orchestration by Inés

Costales

De Rêve is part of

Debussy's song-cycle Proses Lyriques. The cycle

contains four songs, and was composed in 1892-1893. Only

for these four songs Debussy wrote the texts himself.

His decision to use own poetry for a complete vocal work

probably stems on the one hand from his admiration of

Richard Wagner (even though this admiration was

paradoxical), and on the other hand from his idea that

he was a writer - an idea he has kept throughout the

1890s.

Debussy's texts adhere closely to

the Symbolist poems of Bourget, Baudelaire and Verlaine;

Debussy used poems of these symbolists in earlier works

already. In Proses Lyriques Debussy

deliberately chose to write in free verse, thus avoiding

any metric constraint. As Debussy claims that rhythmic

prose is superior to classical poetry, he indeed

underlines that he is faithful to symbolist aesthetics.

Nuit d´eté could have been

composed around the same time. I took Proses

Lyriques as a point of departure, though I also

used earlier and later Debussy songs as references and

sources of inspiration. I chose to set Paul Bourget's

poem Nuit d´eté to music, a poem from Les

Aveux, a collections published in 1882.

As the cycle Proses Lyriques

was composed in the same period as Debussy was

completing both his String Quartet and the

Prélude à l´après-midi d´un faune, I took the

instrumentation of the Prélude for the

orchestration of both De rêve and my own song,

Nuit d´eté. Even though no orchestral score by

Debussy of De rêve is existent, many annotations

in the voice-and-piano manuscript may reveil that

Debussy had an orchestrated version of De rêve in

mind from the beginning.

| Nuit d’eté (Paul Bourget) |

Ô nuit, ô douce nuit d'été, qui viens à nous Parmi les foins coupés et sous la lune rose, Tu dis aux amoureux de se mettre à genoux, Et sur leur front brûlant un souffle frais se pose! Ô nuit, ô douce nuit

d'été, qui fais fleurir Ô nuit, ô douce nuit

d'été, qui sur les mers Ô nuit, ô douce nuit

d'été, qui parles bas, |

| De rêve… (Claude Debussy) |

La nuit a des douceurs de femme, Et les vieux arbres, sous la lune d'or, Songent! À celle qui vient de passer, La tête emperlée, Maintenant navrée, à jamais navrée, Ils n'ont pas su lui faire signe... Toutes! Elles ont passé: Les Frêles, les Folles, Semant leur rire au gazon grêle, Aux brises frôleuses la caresse charmeuse des hanches fleurissantes. Hélas! de tout ceci, plus rien qu'un blanc frisson... Les vieux arbres sous la lune d'or Pleurent leurs belles feuilles d'or! Nul ne leur dédiera Plus la fierté des casques d'or, Maintenant ternis, à jamais ternis: Les chevaliers sont morts Sur le chemin du Gra al! La nuit a des douceurs de femme, Des mains semblent frôler les âmes, Mains si folles, si frêles, Au temps où les épées chantaient pour Elles! D'étranges soupirs s'élèvent sous les arbres: Mon âme c'est du rêve ancien qui t'étreint! |

|

|

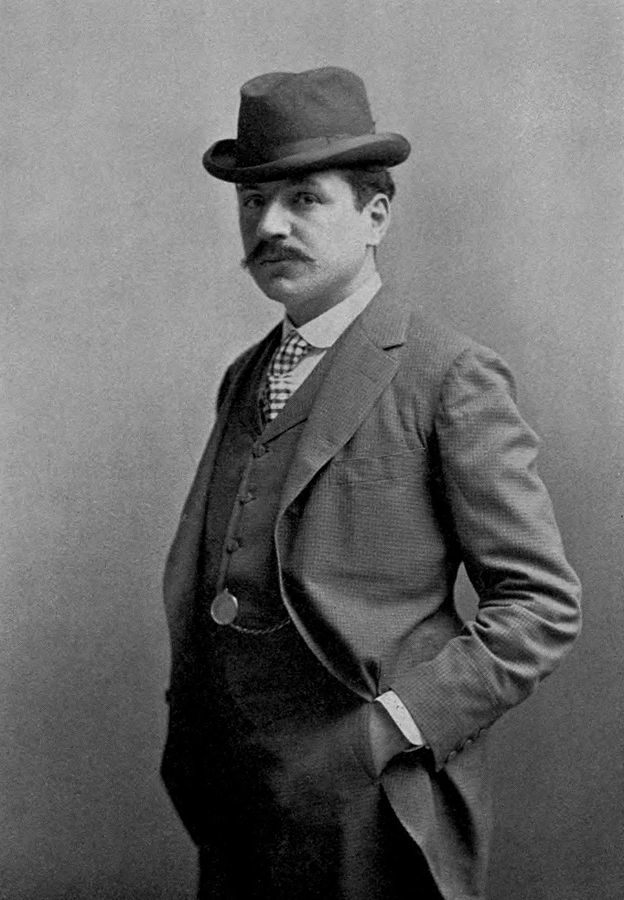

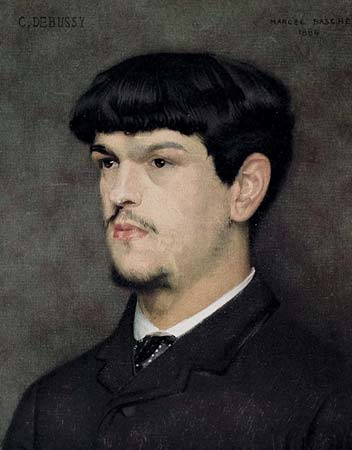

| Paul Bourget in 1899 | Debussy, painting by

Marcel Baschet, 1884. Versailles Museum |

| What’s a style study? |

| Program |

| Members of the Orchestra |

| Alberto Martín

Entrialgo/ Albeniz: Launcelot, Overture and Duet |

| Aljoscha Ristow: Overture: Ariadne und Theseus |

| Inés

Costales / Debussy: Nuit d´eté De rêve... |

| Davide Catina: Overture: Gaston de Foix |

| [ back to top ] |

Overture: Gaston

de Foix

16th Century Italy was a theatre of constant wars between national and continental forces, all concerned with the political balances within the strategically vital Peninsula.

A central episode of these so-called Italian wars was the War of the League of Cambrai (1508-1516), which saw as its main operating powers the Republic of Venice, the Papal States and France; other states and kingdoms such as England, Spain, the Duchy of Milan, and the Holy Roman Empire took part in the conflict, supporting or fighting against the three main powers.

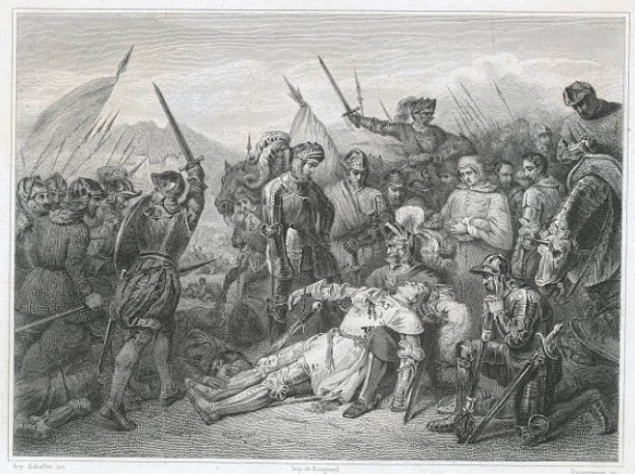

|

| Death of Gaston de

Foix at the Great Battle of Ravenna (1512) |

Gaston de Foix Nemours, nephew of king Louis XII of France (and brother of Germaine de Foix, second wife of Ferdinand II of Aragon), went down in history as one of the main figures of the conflict. In 1511, at the age of 21, he was appointed head of the French army by king Louis XII. His courage and charismatic power have been reported by a great number of historians of the time, as well as writers, poets and philosophers.

After having sacked the Lombardic city of Brescia on the 19th of February 1512, where he defeated the Venetian army, Gaston de Foix moved forward to the city of Ravenna. On Easter Sunday (11th of April) he fought the Spanish-Papal coalition in one of the most ferocious battles of the time.

The battle was won by the French, but Gaston was fatally killed during one of the last cavalry charges; his death was a terrible loss to his army and, according to reports, determined the future political balances of Italy and continental Europe.

This display of events, culminating with the Battle of Ravenna, could very well fulfill the dramatic needs of a 19th century opera composer. The political element, and the Renaissance-based plot, were common stylistic features within Italian operatic aesthetics of the 19th century. This Concert Overture, with its half-programmatic content, focuses on the figure of Gaston de Foix and is inspired by the composers of the 19th century operatic tradition, starting from Verdi and Tchaikovsky, and more on the background Wagner and Weber.

|

| Agostino Busti

(1483-1548): Detail of Monumento Funebre di Gaston de Foix Museo d'Arte Antica del Castello Sforzesco, Milano. |

| [ back to top ] |

|

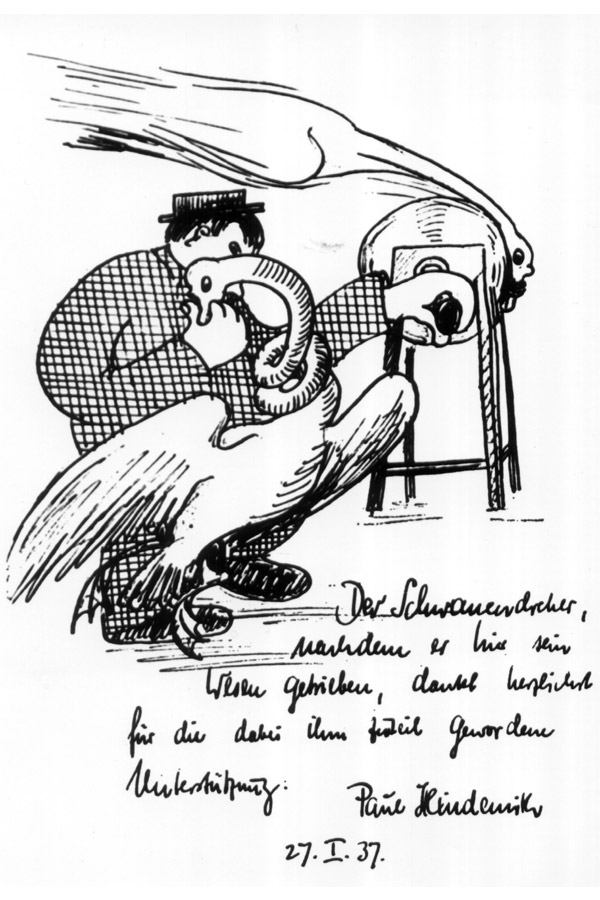

| Der Schwanendreher, drawing by Hindemith |

Upcoming Philharmonic Friday 2017-2018:

Friday, March 16, 12.30 Bernhard Haitinkzaal

Paul Hindemith, Der Schwanendreher

Concerto after old Folk Songs for Viola and small Orchestra

Orchestra conducted by Ed Spanjaard; soloist: Take Konoé

| [ back to top ] |